ISIS Wins Because The Iraqi Army Won’t Fight For A Country That No Longer Exists

AS ISIS butchers its way across Iraq, we wonder what happened to the Iraqi Army?

Peter Beaumont looks at the arsenal:

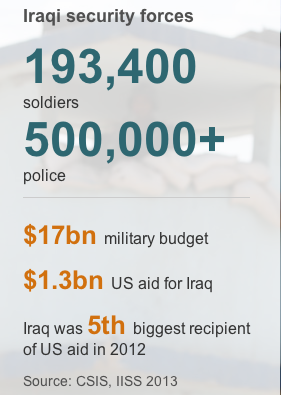

After Iraq’s armed forces were disbanded following the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003, the United States and its allies committed more than $25bn to training and building a new military. With more than 250,000 frontline troops (not counting paramilitary police units), on paper at least the Iraqi military should be effective. It is equipped with almost 400 tanks including US M1A1s and Russian T- series tanks including the T-72. It also has more than 2,500 armoured fighting vehicles and 278 aircraft, including drones, transport aircraft, amphibious aircraft and 129 helicopters.

ISIS has up to 6,000 fighters.

Did we leave behind a good, well-trained Army?

During Operation Telic 13, the codename for British operations in Iraq since the invasion in March 2003, British troops have focused mainly on mentoring the Iraqi army, in particular the 14th Division. “I think we can go with our hands on our hearts, holding our heads high, very proud of what people have achieved here over the last six years,” says outgoing Major General Andy Salmon.

…

“The British here truly have an understanding of an insurgency-rich environment. The steps they have taken and set in place have set American and coalition forces up for success as we partner with the Iraqis here,” says Col Stanford.

Who esle trained the Iraqis?

Borzou Daragahi wrote for the Post-Gazette in 2003:

KIRKUSH, Iraq — A noisy column of green camouflage heralds the coming of the new Iraqi Army’s first recruits. The would-be soldiers — young and middle aged, Kurdish, Arab and Turkoman — march in formation, launch ambushes, fire their weapons and take instruction on the ethics of being good soldiers.

The United States occupation authority, proudly displaying the battalion-size set of recruits for the international media earlier this month, hopes they will eventually grow into a pro-American military that will defend the country from foreign enemies and prevent domestic strife.

But to train them in these critical tasks, the United States isn’t turning to its own armed forces but to a group of gray-suited specialists under contract from the Vinnell Corp., a subsidiary of American defense giant Northrop Grumman. Vinnell is one of more than a dozen private military companies, often called PMCs, hired by the Pentagon to augment U.S. forces in Iraq in ways that have occasionally raised the eyebrows of real soldiers and occupation officials.

“The Iraqi army is such an essential component for the future of Iraq in terms of avoiding civil war,” said Rex Wempen, a Baghdad-based security consultant and former Special Forces operative. “It shows how embedded the PMCs are in the thinking of the Department of Defense that they would use them to train that army.”

Brad Hardy is an active duty Army major. As a battery commander in Kirkuk, Iraq, in 2009, he helped train Iraqi police. He writes:

The problem is that despite all of the regional-specific training the conventional Army received and military-to-military training it applied between 2007 and 2011, little of it can be correlated to any substantial growth within the ISF. The evidence is in the current news. There are a number of reasons why the Army was largely unsuccessful in preparing ISF for the fight it now faces. One may be that the training we offered was centered on how to operate as the U.S., not Iraqi, Army. Another may be that when the Iraqi showed any tactical ability, it was more to impress the American noncommissioned officer standing behind him than to defend against an opposing tribe or political belief. A third is that the American soldier’s planning doctrine is too Western and incongruent with Eastern methods. Fourth, despite our best efforts over the years, courage and effective, trustworthy leadership may not be trainable. Overall, no matter how culturally savvy we were back in the OIF days, the training and partnering we conducted never truly translated. The military decision-making process and patrolling may have been explained in Arabic, but never fully modified from the original Western school of thought for Iraqis to fully absorb.

The New York Times sees a fractured military:

The stunning collapse of Iraq’s army in a string of cities across the north reflects poor leadership, declining troop morale, broken equipment and a sharp decline in training since the last American advisers left the country in 2011, American military and intelligence officials said Thursday.

Four of Iraq’s 14 army divisions virtually abandoned their posts, stripped off their uniforms and fled when confronted in cities such as Mosul and Tikrit by militant groups, principally fighters aligned with the radical Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, or ISIS, the officials said.

The divisions that collapsed were said to be made up of Sunni, Shiite and Kurdish troops. Other units made up of mainly Shiite troops and stationed closer to Baghdad, the Iraqi capital, were believed to be more loyal to the government of Prime Minister Nuri Kamal al-Maliki, a Shiite, and would most likely put up greater resistance, according to the officials…

“This is not about ISIS strength, but the Iraqi security forces’ weakness,” said a former senior American officer who served in Iraq. “Since the U.S. left in 2011, the training and readiness of the Iraqi security forces has plummeted precipitously.”

The retired officer said the militants’ fast-moving advance south was more a reflection of the lack of resistance by Iraqi forces than the effectiveness of ISIS and its confederates.

“If the cops abandon a city, the criminals are going to run rampant,” the officer said.

In 2007, one soldier wrote about that Iraqi army’s sense of unity:

If Shia identity inhibited the effectiveness of the Iraqi Army, then the obvious answer would seem to be to recruit more Sunnis. Accordingly, the Marines made recruiting Sunnis, particularly in early 2006, a priority. Unfortunately, recruiting Sunnis has proved quite difficult. In early 2006, the Iraqi Ministry of Defense permitted 6,500 Sunnis from Al Anbar to be recruited to serve throughout the country. The first recruiting effort took place at the end of March, when the Marines enlisted 1,017 men, largely from Falluja. Unfortunately, the Sunni recruits were led to believe they would be serving near their homes, and were given further assurance by the mayor; by all accounts, his assurances had induced many to volunteer.

On April 30, the new soldiers graduated from training at Camp Habbaniyah. During the ceremony, replete with Coalition and Iraqi generals, it was announced that many would be deployed outside Al Anbar. Yelling and throwing their uniforms to the ground, 600 of the newly trained soldiers refused to deploy. Not only did they feel cheated, but they also feared sectarian retribution if they joined predominantly Shia units outside the Sunni Triangle; many told U.S. officers they would be attacked if they left Al Anbar. The mayor of Falluja supported the recruits, telling Coalition officers, “As long as I am receiving corpses from Baghdad, I will not send soldiers there.” In the end, more than 600 of the 1,017 recruits deserted. If Sunnis refuse to serve, there is no way we can expect the Iraqi Army to bridge sectarian differences and handle the insurgency. Indeed, the only way Sunnis will ever support the army is if it loses its structure as an integrated and national force and becomes a set of locally recruited brigades–no different from the police or a militia.

Why fight when you get no support? This from 2007:

Though Iraqis fight alongside Americans, their destinies diverge upon injury. Wounded U.S. soldiers are typically flown within one day to a first-class military hospital in Germany and arrive within 72 hours at Walter Reed Army Medical Center, where amputees receive extensive rehabilitation and prosthetic limbs at a cost to taxpayers of $58,000 to $157,000 per soldier, according to a 2006 study by the American Enterprise Institute-Brookings Institution.

Decent military hospitals existed under Saddam Hussein, but they were looted during the war and their doctors fled. So while some seriously injured Iraqi soldiers now receive initial treatment at sophisticated U.S. military facilities in Iraq, they must recover in public hospitals where medicines and highly trained staff are scarce. There is one military prosthetics clinic in the country, little in the way of mental health services and no burn center.

“U.S. soldiers have access to rehab and prosthetics that are obviously better than what Iraqis have,” said Maj. Brian Krakover, 32, emergency room physician at the U.S. military hospital in Baghdad’s Green Zone. “It really makes the sacrifice that these guys make so significant, knowing that if they get hurt they don’t have the potential future that, say, a 20-year-old U.S. soldier who gets his legs blown off would have. They are really sticking their necks out here.”

Now hospitals are being bombed.

During the recent Palestinian-Israeli conflict, Israel has been harshly criticized for its strikes on Gaza’s hospitals [The Wall Street Journal’s Nick Casey posted a photo of a Hamas spokesman being interviewed from a room in the hospital along with this tweet: “You have to wonder (with) the shelling how patients at Shifa hospital feel as Hamas uses it as a safe place to see media.”]. Meanwhile, in the self-declared Islamic Caliphate straddling Iraq and Syria, violence surges while fewer and fewer doctors and hospitals remain functional. The deliberate targeting of hospitals and doctors in the theater of war has become a new, deadly strategy.

However, this worsening humanitarian crisis in neighboring countries garners a fraction of the outrage directed towards Israel. As war rages on, millions in Syria and Iraq will continue to die unnoticed, in battle, or from easily preventable ailments that have gone untreated. Long after the cease-fire finally sticks between Israel and Hamas, the vulnerability of patients and their doctors in Iraq and Syria will only grow…

Following the U.S. invasion in 2003, 78 percent of Iraq’s health professionals in Baghdad alone had fled by 2007. Before the invasion, Iraq had approximately 34,000 physicians; by 2006, 18,000 remained. Those doctors who stayed were forced to work in difficult conditions: More than 80 percent of physicians at Iraq’s emergency hospitals report being assaulted. Many have paid the highest costs: by 2006, 2,000 Iraqi doctors had been killed.

Once renowned for its top-notch health care, Iraq has seen its health system steadily collapse. Already hobbled by sanctions before the invasion, 12 percent of all Iraqi hospitals were destroyed, 7 percent were looted, a third of family planning centers were destroyed and leading public health laboratories in Basra and Baghdad were also destroyed after the fall of Iraq. In the facilities that have survived, 65 percent of the remaining equipment is considered useless. Patients needing advanced care have to leave the country.

Why fight for Iraq if Iraq doens’t really exist?

Posted: 14th, August 2014 | In: Reviews Comment (1) | TrackBack | Permalink