Higher Education Is All About Debt: Pricking The University Bubble

DID you sign up for Bachelor of… degree? Did you borrow money to pay your fees? The UK is not America – yet, where sky-high college fees are an affront to ideal of freedom. B ut it;s getting that way. Higher education is big business. And you owe it:

It is likely that there are at least as many adult Americans with student-loan debts outstanding as there are living bachelor’s degree recipients who ever took out student loans. That’s right: as many debtors as degree holders! How can that be? First, huge numbers of those borrowing money never graduate from college. Second, many who borrow are not in baccalaureate degree programs. Three, people take forever to pay their loans back.

Some retire before the loan the paid off.

That pension pot is shrinking:

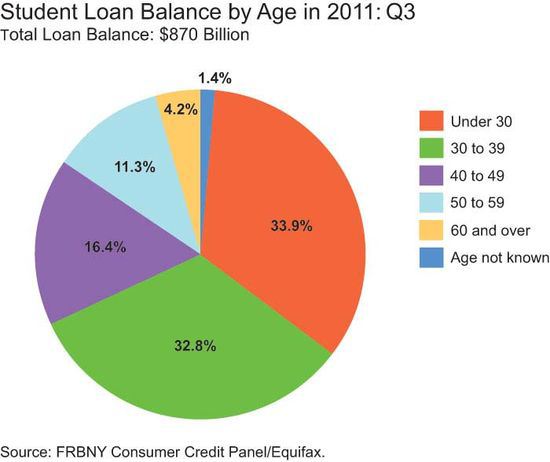

“A]n estimated two million Americans age 60 and older … are in debt from unpaid student loans, according to data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. Its August Household Debt and Credit Report said the number of aging Americans with outstanding student loans had almost tripled from about 700,000 in 2005, whether from long-ago loans for their own educations or more recent borrowing to pay for college degrees for family members. . . . While older debtors account for a small fraction of student loan borrowers, who have accumulated nearly $1 trillion in such debt, the effect of owing a constantly ballooning amount of debt but having a fixed income can be onerous, said Senator Bill Nelson, Democrat of Florida, chairman of the Senate Special Committee on Aging.”

Not everyone pays it off. J.D. Tuccille:

Unshockingly, while defaults decline for credit card debt, mortgages and auto loans, they’re on the rise for student loans. “At 10.9 percent, the second quarter 2014 delinquency rate on student loans was more than three times that of mortgages and auto loans, and more than 3 percentage points higher than the rate of serious delinquencies on credit cards.” Apparently, young grads with overpriced sheepskins and no decent jobs in the offing have trouble meeting the tab.

That affects housing. John Aravosis observes:i

8% fewer homes will transact than normal in 2014, purely due to student debt. … Our conclusion is that 414,000 transactions will be lost in 2014 due to student debt. At a typical price of $200,000, that is $83 billion per year in lost volume.

But if you can’t afford to buy a house, don’t:

When legislators and activists say that we need low-down-payment loans because most people couldn’t possibly save up for a 20 percent down payment, what they’re really saying is that people can’t actually afford to buy a house. Helping them to go buy one anyway is not a great idea; it will work out well for some, to be sure, but it will have tragic consequences for others, and for the housing market as a whole if there’s another downturn. We just spent six years learning, the very hard way, that you can’t borrow yourself rich. That knowledge is too expensive to throw away so easily.

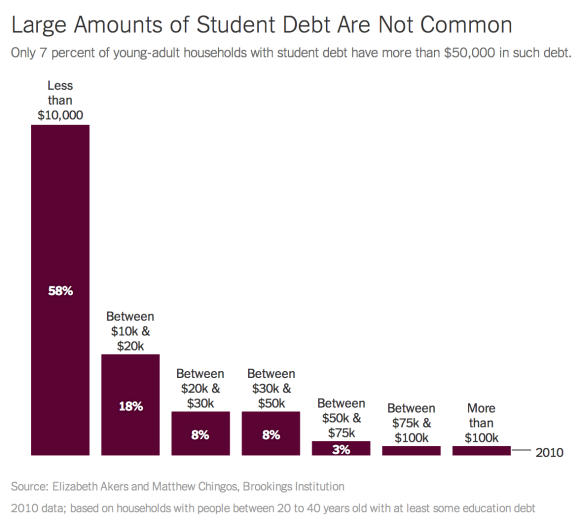

Maybe the amount of student debt is low?

Jordan Weissman looks at the demographics:

If you talk to people who study education policy for a living, they’ll tell you that the real victims of student debt aren’t English grads who took out a bit too much money to attend the University of Michigan or Oberlin. Those kinds of borrowers usually end up just fine.

However, there is a huge contingent of working-class and minority students –some of whom are among the first of their families to attend college – who are getting chewed up by student debt. These are young people, and increasingly older adults, who might not have gone to college 20 or 30 years ago, but do now because the economy is brutal for job-seekers without a degree. They borrow for school, often to pay the inflated tuition at an unscrupulous for-profit institution or little-known vocational school, then frequently drop out. Suddenly, they find themselves in debt, with no degree and no guidance on how to manage their loans.

Maybe not. Pew:

In the early ’90s, only among graduates from low-income families did a majority of graduates finish college with student debt. Now, solid majorities of graduates from middle-income families (both lower-middle and upper-middle) finish with debt, and half of students from the most affluent quartile of families do the same. … Among recent college graduates who borrowed, the typical amount of cumulative student debt for their undergraduate education increased from $12,434 for the class of 1992-93 to $26,885 for the class of 2011-12(figures adjusted for inflation). The increase in the median amount of debt by newly minted borrowers between the class of 1992-93 and the 2011-12 varied somewhat by the graduates’ economic circumstances. But regardless of family income, the typical amount owed at graduation increased about twofold over this time period.

The big money comes from overseas students:

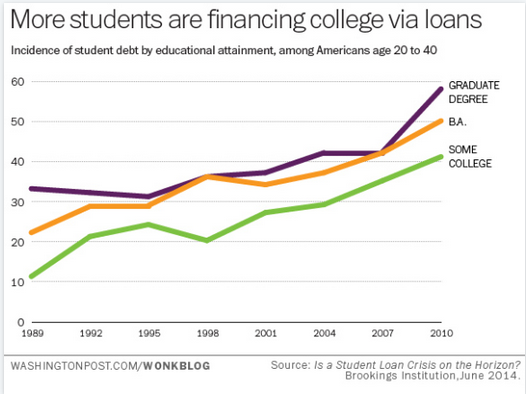

Christopher Ingraham notes:

The big story in student debt over the past 20 years is not – and never should have been – the few people taking on huge debt burdens, but rather that the share of all students graduating with any student debt has risen sharply:

In 1989, 22 percent of households headed by twenty-to-forty-somethings with a degree were saddled with student loan debt. That figure more than doubled by 2010, standing at 50 percent. It’s likely climbed even more since then. That number is probably an underestimate, too. … Another important consideration is that the data above only go back to 1989. If we could extend it further, to the 1960s and 1970s, when Boomers were graduating, we’d likely see even lower rates of student debt back then. This is the reason why it feels like student debt is everywhere these days –compared to the ’60s and ’70s, it is everywhere

Bill McMorris sees a student loan bubble:

The lie that props up our Big Education regime is that the GI Bill, which paid for World War II veterans to attend college, produced the upward mobility and economic boom of the postwar period. It’s a heartwarming story, the veteran who would have been a dust farmer but for the grace of government generosity. But it just isn’t true. Only one out of every eight returning veterans attended college. The rest, the vast majority, benefited from something even more egalitarian: aptitude testing. The format favors raw talent above all else, allowing companies to hire high-potential candidates from any background and groom them to fit the company’s needs.

These tactics came to commerce from a familiar source.The armed services were forced to process hundreds of thousands of recruits during the war, and in order to filter and assign soldiers, the government developed aptitude tests. Businesses witnessed the U.S. defeat the two most efficient peoples known to man, thought there must be something to this whole testing thing, and followed suit. The chief hiring metric in the postwar era was not whether someone had a degree, but whether he had the aptitude that would enable him to succeed. Every industry from blue-blooded high finance to immigrant-heavy manufacturing employed testing to determine who would rise through the ranks, regardless of lineage, heritage, or education. Testing enabled men who set out to be blue-collar workers to ascend based solely on their ability. . . .

Two years ago I interviewed Den Black, a former automotive engineer at GM supplier Delphi whose pension was slashed to speed up the auto bailout. His backstory interested me nearly as much as his grievance with the Obama administration. A few years before the Supreme Court issued the Griggs decision, he set out to join his brother as a line-worker at General Motors. He hadn’t been the best student, didn’t care much for school, but submitted to the hiring exam. The test revealed that he had an advanced understanding of physics and mathematics. Within a few years, he was given the opportunity to take the entrance exam to General Motors University. After two years at GMU, where he combined shiftwork with education, he emerged an engineer in management. It’s no bachelor’s degree, but judging by the patents he helped generate, it was a worthy investment.

The Griggs decision has made that organic rise through the ranks impossible, as disparate impact left businesses liable for those who failed to pass hiring tests.

“Most legitimate job selection practices, including those that predict productivity better than alternatives, will routinely trigger liability under the current rule,” Wax wrote in a 2011 paper titled “Disparate Impact Realism.”

The solution for businesses post-Griggs was obvious: outsource screening to colleges, which are allowed to weed out poor candidates based on test scores. The bachelor’s degree, previously reserved for academics, doctors, and lawyers, became the de facto credential required for any white-collar job.

So. Still want a college degree..?

Posted: 24th, October 2014 | In: Money, Reviews Comment (1) | TrackBack | Permalink