Victims of Batang Kali denied answers: murder in the name of war

THERE will no enquiry into the shooting at Batang Kali, Malaya, on December 11 and 12, 1948. Twenty-four unarmed Chinese workers on a Scottish-owned plantation rubber plantation were killed by a 16-strong platoon of Scots Guards in the so-called “Malayan Emergency”.

THERE will no enquiry into the shooting at Batang Kali, Malaya, on December 11 and 12, 1948. Twenty-four unarmed Chinese workers on a Scottish-owned plantation rubber plantation were killed by a 16-strong platoon of Scots Guards in the so-called “Malayan Emergency”.

Every man in the village of Batang Kali was killed. The women and children were placed in a truck and driven away. Then the shooting started.

Lim Ah Yin was 11:

“We found my father’s body by the riverbank. The smell was terrible. They were lying face down, in small groups of four or five.”

A soldier was quoted:

“Once we started firing we seemed to go mad . . . I remember the water turning red with their blood.”

The soldiers then burnt the village to the ground.

The State says the Scots Guards were acting under the directions of the Sultan of Selangor, not the British Government. So. The Brits are in the clear. Selangor was a Protectorate not a colony.

George Kydd, was a member of the Scots Guards patrol. In 1970 he recalled:

“The bandits were then shot but I’m sorry I must tell you the truth, they were not running away. There was an inquiry later on and I’ve got to go along with this, we were told before going in to tell the same story, that is that the bandits were running away when they were shot … I don’t remember who told us to tell this story but it was a member of the army.”

Solicitor John Halford, represents relatives of the dead:

“We are appealing. As long as the injustice remains, the families will be pursuing legal action.”

Sir John Thomas, president of the Queen’s Bench Division of the High Court, explained:

“In our judgment, the decisions of the secretaries of state were ones that took into account the relevant considerations and were not unreasonable. here are no grounds for disturbing their conclusion. In our judgment, they had regard to the relevant factors and weighed them carefully and reached a conclusion which it was plainly open to them to reach.”

In June, Nick Harvey, Armed Forces Minister, told the Times:

“The British Government acknowledges that something very bad took place, but we are sceptical 64 years later that it is going to be possible to discover any more. But you should not construe the British government position as meaning that there is a denial that anything bad happened, because that’s beyond contention.”

A Foreign and Commonwealth Office spokeswoman said:

“Accounts of what happened conflict and virtually all the witnesses are dead. In these circumstances it is unlikely that a public inquiry could come up with recommendations which would help to prevent any recurrence.”

Well, if you wait long enough, all the witnesses die… A minute from the AttorneyGeneral Secretariat in August 1970, said “matter will probably now remain buried in the public mind in perpetuo and [be] quietly forgotten”.

The Times reported on a previous investigation:

Six members of the Scots Guards patrol that killed the villagers in 1948 at the height of the Malaya Emergency told British police in 1970 that “the killings were arranged and systematic rather than a reaction … to an escape attempt”. The detectives were preparing to visit Malaysia to interview survivors of the incident at Batang Kali before returning to interview, under caution, the senior Scots Guards officers alleged to have given the kill orders. But in June 1970, days after the Conservatives had seized power from the Labour administration, the detectives were ordered to halt the investigation because of what they described as a “political change of view”.

The victims of Britain’s My Lai continue to look for answers…

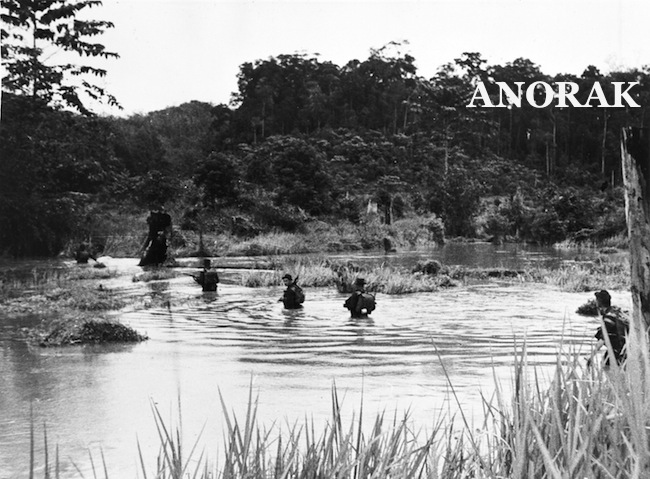

Scots Guard of the Second Battalion, G Co mpany, wade waist deep through muddy swamp water during an anti-guerilla operation in Pahabg, Malaysia, in January 1950. (AP Photo)

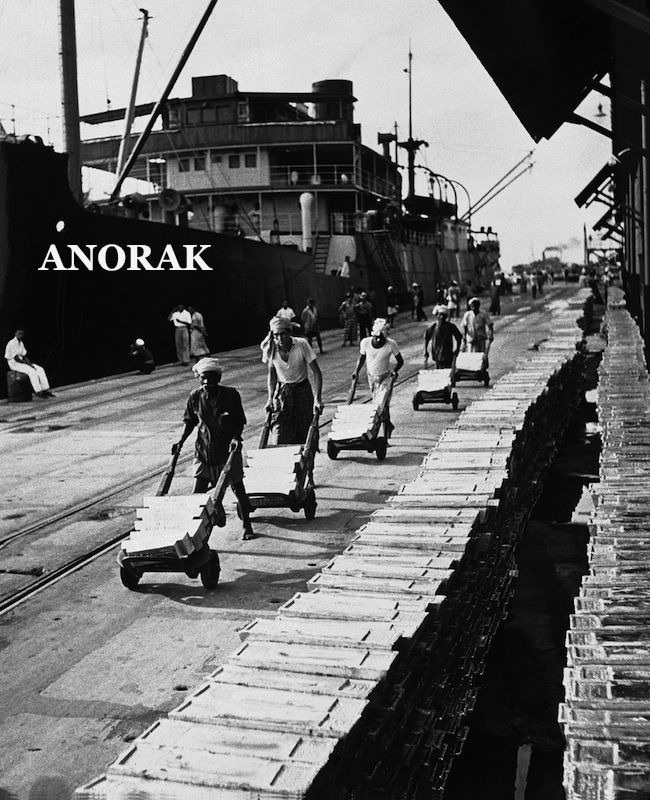

Workers pile up 99% pure tin ingots along Penang dock in Malaysia on August 6, 1941. (AP Photo)

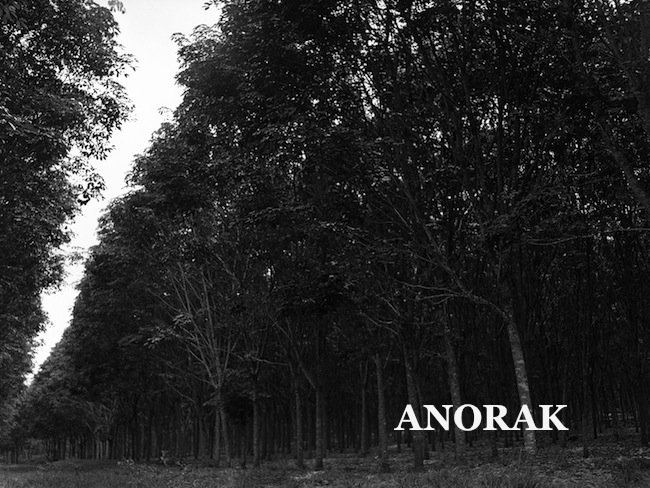

The rubber situation in Malaya is much brighter than was at first expected. A British military spokesman estimates that of the three and half million acres of rubber plantations, not more than five per cent have been destroyed by the Japâs. In some rubber plantations the trees were destroyed for agricultural purposes by the Japâs. The plantations, owing to shortage of labour are at a standstill and have not been worked during the Jap occupation, although experts bay the trees are in good condition. Official figures disclose that 33,000 tons of rubber in bulk have been found in Malaya and will be shipped abroad as soon as possible. Rubber trees growing in good condition, undisturbed by the Japanese, in one of the vast plantation in Malaya, Singapore on Nov. 4, 1945. (AP Photo)

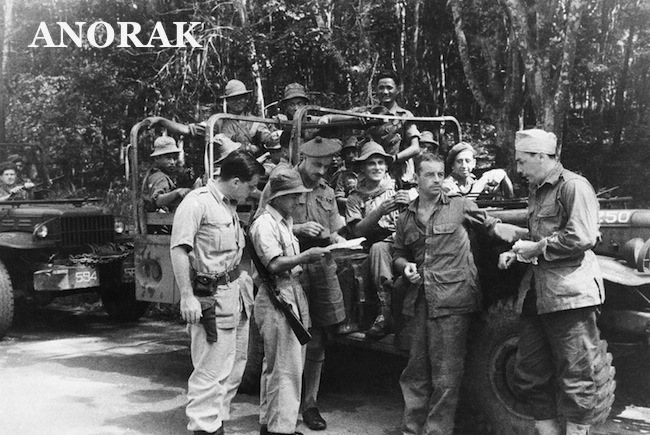

Men of the 1st Sea forth Highlanders, the Devonshire Regiment, the Gurkhas, the Royal Artillery, the Singapore police and the 4th Ferret Group took part in the recently conducted ‘Operation Rugger’ tempt to clear suspected terrorists out of the jungle. A team from the 4th Ferret group study their plans before going into action.

A native hut blazes in the jungle near Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia on July 10, 1948, after being set afire by Gurkha troops and police in their sweep against communist insurgents. No huts were left in the area where the bandits had concentrated. (AP Photo)

Posted: 4th, September 2012 | In: Reviews Comment | TrackBack | Permalink