Listen To All Parts Of Robert Ashley’s Perfect Lives – The Televised American Opera

ROBERT Ashley (1930-2014). The composer was 83.

Kyle Gann, who recently wrote a biography said of the Michigan-born composer, who in 1958 created the Cooperative Studio for Electronic Music , a pointer to his eperiments with audio synthesis.

“Bob was one of the most amazing composers of the 20th century, and the greatest genius of 20th-century opera. I don’t know how long it’s going to take the world to recognize that.”

Thanks to the internet, the past never goes away. You can hear some of Ashley’s work in full.

In 1997, he spoke to Furious:

PSF: How did you decide to make your works as all being operas?

In 1975, there were no operas in America. I was interested in opera and it seemed to me that the only possible theatre for contemporary opera would be television. So I started working towards a kind of television kind of opera. I started designed the work so that it would be usable on television. I think it’s still true.

PSF: How did you see television as an ideal medium for operas?

It’s contemporary. It’s new. Many more people watch television than go to opera houses. There aren’t any opera houses in the United States. The possibilities for contemporary opera are very small. I thought when I started, it looked more promising (to work with television). Now, in the last few years, television has become much more conversative. But I still think there’s going to be a marriage of television and some form of opera. It might not happen in my lifetime but I still think it’s inevitable. The whole idea of the opera house is so dated anyway. It’s such a nineteenth century idea. Because of that probably, there aren’t any to speak of (maybe 3 or 4). It doesn’t really allow the idea of opera to really grow. I thought if I could get television interested in opera, it would make a kind of new thing that would allow composers to build a whole new repertoire.

It was more promising fifteen or twenty years ago than it is now. The first opera I did, Music With Its Roots in Ether (1976), has been broadcasted a lot. The next one I did, Perfect Lives (1980), was produced by Channel 4 in Great Britian and was shown there for two years and then throughout Europe but only parts of it have been broadcast in the United States. Now in ’97, television is so conserative that it doesn’t look promising. But I think it’ll change back. I think it’ inevitable that there has to be some new genre in television. Television goes through these periods of incorporating new things. First there was live comedy then there were soap operas then there was news and now there’s a lot of television about sports. We went through a period of MTV with pop music videos too. Television always needs new materials and it’s just a matter of time until there’s the right audience for new work that’s not just pop music. When that happens, it’ll be a very good time for composers to do serious big, narrative pieces.

PSF: Why do think there has been resistance to this kind of idea in American television?

Because they’re stupid I guess. Opera on television in Europe is very important. If you think about it in the broadest sense: a lot of the dramas made in India with music are practically operas. They’re not sung but they have a very big appeal. I don’t know why American television people are so stupid but at the moment, they just seem to have some sort of a block. They just do what they do and they do it for a certain number of years. Then it wears out and they try something else. It’s just a matter of time I think.

Brian Robison, of Cornell University, has posted on YouTube 4 American Composers, directed by Peter Greenaway in New York in 1985.

Compared to Meredith Monk and Robert Ashley, John Cage and Philip Glass are household names, yet their relative fame frequently turns on the persistence of misconceptions. All too often, even scholars who might be expected to know better portray Cage as either charlatan or nihilist. Critics in the 1980s tagged Glass’s music as “classical music for people who don’t like classical music,” suggesting his shrewd exploitation of the yuppie market. Director Peter Greenaway and producer Revel Guest weave representative musical excerpts with interviews to present the personalities more accurately, and, in so doing, establishes a broader context for listening. Perhaps the most striking revelation of these documentaries is that such notorious iconoclasts are so soft-spoken in person (compared to the shy, halting Ashley, the loquacious Monk seems downright assertive).

Ashley’s TV opera Perfect Lives was reviewed by Frieze:

As living and breathing musicology in practice, Perfect Lives explores how storytelling creates music and – tangentially – how American social models grew in tandem with musical forms from Europe and Africa. Built into the very structures of how it was written and is performed – there is no definitive score, only the libretto, some diacritic and harmonic indications, and a set of intricate time signatures to follow – Perfect Lives is about the sociability of music. Ashley realized Perfect Lives over a period of years with a number of close collaborators. (‘I only work with geniuses,’ he says. ‘In the end it pays off.’5) In a documentary made by Peter Greenaway in 1983, as part of his ‘Four American Composers’ series, Ashley said he wanted to ‘allow the performers to make musical statements as unpremeditated as speech itself’.

Ashley spoke with Alex Waterman:

What distinguishes traditional opera from any other form of narrative—like religious dramas, for example—is that most operas have a political landscape. This is especially true in Italian and German opera. You get a version of a landscape that has political meaning. I thought about that when contemplating the architecture of the opera house and how it makes those landscapes possible. Of course, that architecture is not available to me, nor would I want it to be. But the landscape has to be there however the opera is presented.

In the best of circumstances, the architecture and the music–for the people—match. But what’s happened in the last 50 to 100 years is that the music has outgrown the architecture. The instruments are old, the ideas are old—everything’s so old; it’s boring, you know? There is no architecture to deal with what we’re talking about here. I thought, There’s got to be one. And it occurred to me that our architecture might be the imaginary space behind the surface of the television screen. In other words, when you watch TV, you see whatever you see, but behind that there’s an imaginary space and maybe that’s the place for the music of our time.

It’s interesting how you can manipulate landscapes with television so that they have meaning. It’s different from having a person singing here, in my living room, which is something of a landscape. If you go outside of the personality of this room, the landscape is all of a sudden dramatically political—it’s a visual demonstration of how things work for everybody. That’s what opera is about. You’re trying to put the story in an appropriate place so that when you see it you say, Oh, that’s what the story is about!…

The landscape in Perfect Lives starts as big as possible, in The Park, and it’s described quite precisely in political terms. And then it goes to The Supermarket, which is not totally indoors. Then you get the ride through the landscape with the lovers eloping and the bank robbers driving to Indiana in The Bank episode, where you are dealing with mixed outdoors and indoors. Next, you enter the most close-range landscape, in The Bar with Rodney and Buddy talking. Then you move out again to a bigger space in The Living Room, which has more imaginary space. At the beginning of that episode, the characters talk about the Sheriff’s Wife as if she were on the South Pole and the Earth were revolving around her.

It is relentless. And mesmeric.

I.The Park (Privacy Rules)

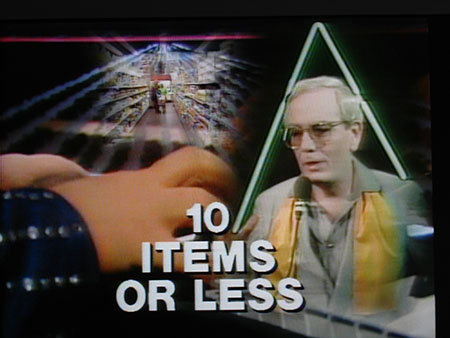

II. The Supermarket (Famous People)

III. The Bank (Victimless Crime)

IV. The Bar (Differences)

V. The Living Room (The Solutions)

VI. The Church (After the Fact)

VII. The Backyard (T’Be Continued)

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

9:00pm “The Living Room” from Varispeed Collective on Vimeo.

6.

5:00pm “The Church” from Varispeed Collective on Vimeo.

7. The Backyard

Posted: 5th, March 2014 | In: Key Posts, Music Comment | TrackBack | Permalink