Trigger Warning: free speech is being attacked and downgraded in Anglo-American culture, says Mick Hume

Anorak asked journalist Mick Hume about his new book, which looks at the highly topical issue of free speech…

Your new book is entitled ‘Trigger Warning’. For those not familiar with the phrase, could you explain its origin and its relevance?

A ‘trigger warning’ is a statement stuck at the beginning of a piece of writing, video or whatever to alert you to the fact that it contains material you may find upsetting or offensive. For example, ‘TW: Islamophobic language’, or ‘TW: references to sexual violence’.

Trigger Warnings took off in US colleges (where student activists want classic works to carry them, suggesting for example that The Great Gatsby should have one along the lines of ‘TW: suicide, domestic abuse and graphic violence’). They have since spread across the Atlantic and the internet. If you are not familiar with ‘TWs’, they are coming soon to a website near you.

For me the mission creep of trigger warnings symbolises the stultifying atmosphere surrounding freedom of expression and debate today. They are like those ‘Here be dragons’ signs on uncharted areas of old maps, warning students and others not to take a risk, not to step off the edge of their comfort zone, not to expose themselves to ‘uncomfortable’ ideas, images or opinions.

What is the book about?

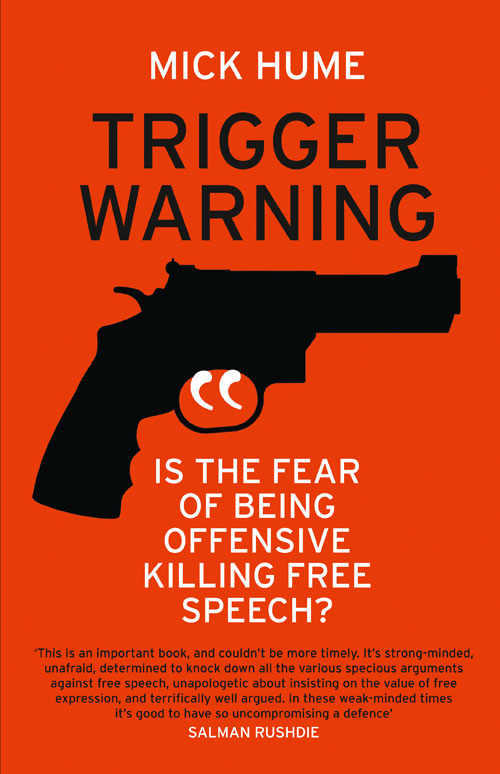

The sub-title of the book rather gives the game away: ‘Is the fear of being offensive killing free speech?’ To which its unsurprising answer is yes, unless we do something about it.

Trigger Warning is about all the various ways in which free speech is being attacked and downgraded in Anglo-American culture today. It describes ‘the silent war on free speech’. It’s a silent war because nobody in politics or public life admits that they are against freedom of expression; all of them will make ritualistic displays of support for it ‘in principle’, as they did after the Charlie Hebdo massacre. In practice, however, they are all seeking ways to restrict freedom of expression, whilst insisting that ‘this is not a free speech issue’, it is merely an attempt to protect the ‘vulnerable’ against offensive and hateful words.

To that end, the book examines the complementary trends towards official censorship, unofficial censorship and self-censorship in the West today, covering everything from online ‘trolls’ to football and comedy as well as more conventional political issues.

Of these three, the most insidious is the informal, unofficial censorship promoted by Twitter mobs and assorted boycott-and-ban-happy zealots. They are a relatively small minority, but they exercise disproportionate influence by preying on the loss of faith in free speech at the top of our societies.

I describe these people as ‘reverse-Voltaires’, who have taken the famous principle linked to Voltaire – ‘I may hate what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it’ – and twisted it into its opposite – ‘I know I will detest what you say, and I will defend to the end of free speech my right to stop you saying it’. They do not want to debate arguments they disagree with, but merely to close them down as offensive. Trigger Warning takes on their most powerful excuses in a section entitled ‘Five good reasons for restricting free speech – and why they’re all wrong’.

What is the main message of the book?

The main message of the book – and I fear it is a ‘message’ book, or ‘polemic’ as we pretentious authors say – is twofold, I suppose. That we have forgotten how important the fight for free speech has been in the creation of something approximating a civilised society, and that we are in danger of giving it up without a struggle. It is not so much that we are losing the free speech wars: we are not even fighting them!

Few of the great advances in politics, science and culture over the past 500 years would have been possible without the expansion of free speech and the willingness of heroic heretics to question everything and break taboos. None of the liberation movements of the recent past could have succeeded without putting the right to free speech at the forefront of their campaigns (which makes it all the more bitterly ironic to see restrictions on free speech being demanded today in the name of protecting the oppressed).

Free speech was never a right to be won once and then put on a shelf to be admired. It always has to be defended again, against new challenges and enemies. The big danger today is that so few are standing up for unfettered free speech against the reverse-Voltaires and their like. Where are the young Tom Paines, JS Mills, John Wilkes’ or George Orwells of our age? Instead we have characters like the US liberal professor who just wrote a (pseudonymous) article about how he is too ‘terrified’ of his ‘liberal’ students to raise a potentially offensive idea or even ask them to read Mark Twain. Time to take a stand before it’s too late.

You have been outspoken about the right to offend. But some people seem to believe they have a duty to offend, and we have seen public examples of this recently. How does your opinion differ from theirs?

I have been writing about the right to be offensive for some 25 years, since the crisis over Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses. It is the cutting edge of free speech. After all, what use is it is we are only ‘free’ to say what everybody else might like? If we defend free speech for those views branded extreme and offensive, the mainstream will look after itself. This is not about offensive language, but opinions – as JS Mill pointed out long ago, the more powerful your opponent’s arguments are, the more offensive you tend to find them!

The importance of that issue was brought into sharp focus by the reaction to the Charlie Hebdo massacre of course. As the book describes, behind the apparent displays of Je Suis Charlie solidarity, the powerful message was that those cartoonists had gone ‘too far’ in offending Islam. Those gunmen might have been inspired by Islamist preachers, but they can only have been encouraged by the loss of faith in free speech at the heart of Western culture.

None of this means, as you mention, that anybody has a duty to offend. The right to be offensive is not an obligation. One problem today is that the response to the conformist culture of You-Can’t-Say-That tends to be a few comedians and others trying to cause offence for the sake of it. That’s infantile and useless. As William Hazlitt wrote, ‘An honest man speaks the truth, though it may cause offence, a vain man, in order that it may”. A good distinction, so long as we remember that the vain man gets the freedom to speak his version of the truth, too.

Trigger Warning: Is the Fear of Being Offensive Killing Free Speech? is published by Collins.

Mick was answering questions put to him by Ed Barrett

Posted: 17th, June 2015 | In: Books, Key Posts, Reviews Comment | TrackBack | Permalink